My mom in the 1980s, shortly after immigrating to Sydney, Australia.

Our new normal

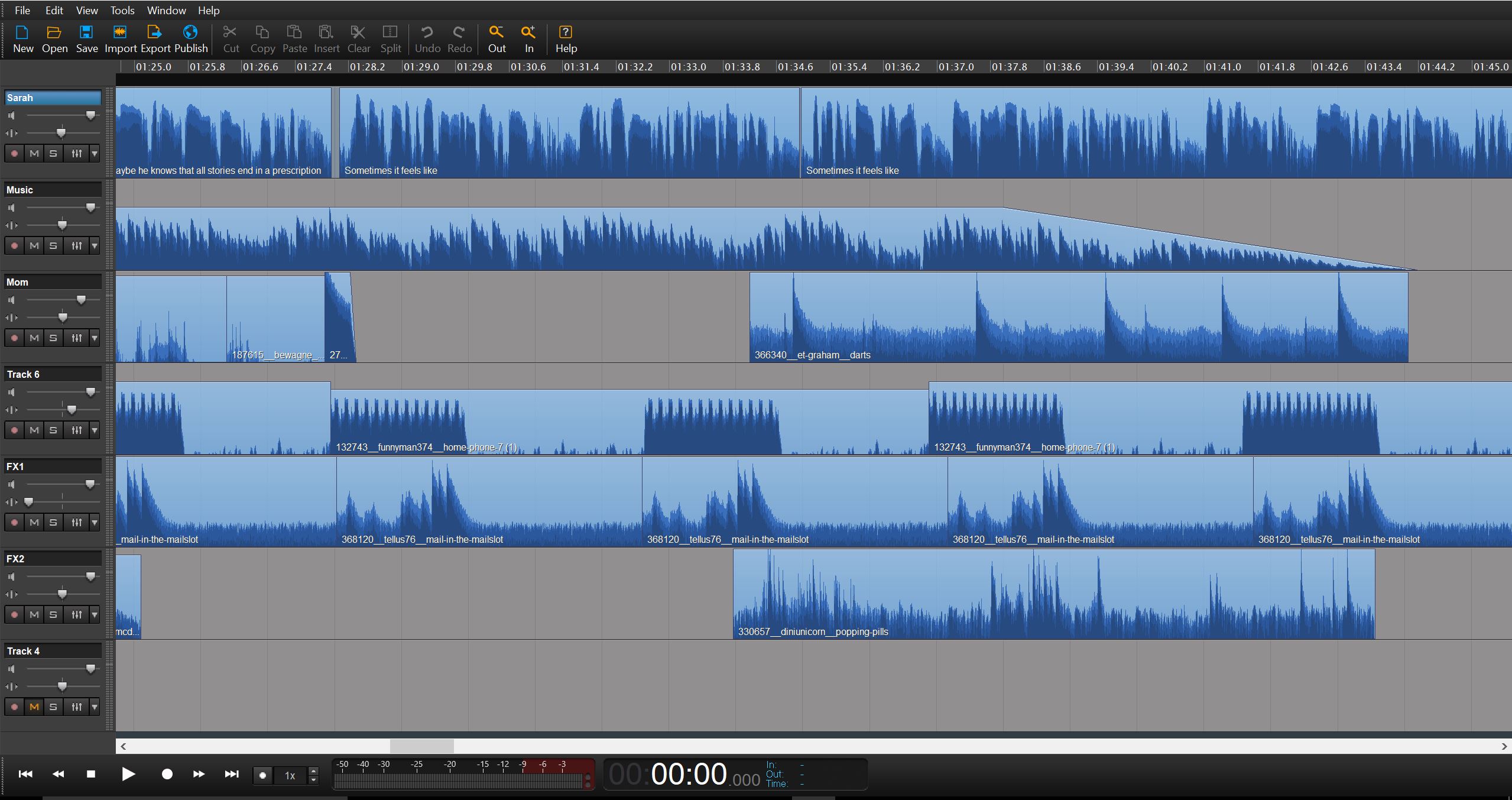

Mom had been diagnosed with major depression, and panic disorder. Together, we began to navigate the day-to-day of living with mental illness.

For me as her caregiver, there was the daily challenge of medication management, side-effect management and helping mom combat her anxiety. I tussled with disability leave, made appointments, and deciphered insurance bills.